Interview with Toni (Johansen) Weisberg

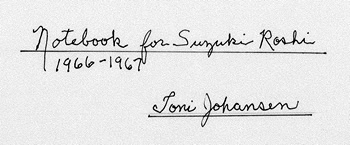

Toni Johansen - 1969 Cuke Podcasts with Toni 1 🔊 2 🔊 Additional notes from Toni after podcasts in 2024 below ↓ 5-29-15 - Acquiring the Beginner's Mind Draft

Handwritten Excerpts from 4th Grade Autobiography by Rhonda Johansen (Toni's daughter) |

|

TONI MCCARTY (JOHANSEN)

October 19, 1995 I took back my maiden name because my brother in the dharma and former husband was also Tony Johansen. I met Suzuki Roshi in 1964 I believe. I had taken acid as therapy after a post partum depression and had an experience so powerful that I decided I needed to find a teacher so that I could live more in tune with what I had experienced and it didn't occur to me to continue taking drugs because it was such a difficult experience though so wonderful. So I went places like the Catholic Church and explained to the priest that I'd had this experience and we're all one and we're all with God and we're all at the center of the universe and everything is happening at once - the eternal present and that he was there too - that it wasn't my experience - it was our experience, everybody's and we were all there and right now in this moment when I was talking to him I wasn't in that consciousness, I just knew it was true because I had experienced it and it was so much deeper than my ordinary experiences that I knew it was true and he told me that was heresy and that's what they used to burn people at the stake for. He didn't say the second part.

Toni and Rhonda Johansen - 1965 I was at that time a housewife with two young children and so every Sunday I'd go looking. I went to the Unitarian Church, I went to the Quakers and the Jodo Shin temple in Palo Alto and I would say what I was looking for and there was a Caucasian Sunday school teacher in his thirties at the later and that fellow said to me you need to meet this Zen master. He comes once a week on Thursday morning to a students house in Palo Alto. It was at the boarding house of Tim Burkett - I went there. We sat in the living room where they had to move the piano and furniture and we sat facing the wall and I thought, this is ridiculous. Reverend Suzuki as we called him only went there a couple of times before he started going to Marian Derby's. We started the same day. For some reason this had been going on for quite a while. There was a morning thing at Tim's and he came back the same evening to Redwood City. Marian and I were driving around in separate cars looking for the address and we stopped and I said are you looking for the Zen talk and she said, "Maybe he gave us the wrong address and this is a test." But we found it. When I went that morning and was sitting facing the wall I thought, this can't be it either. This is too rigid and patriarchal and Japanese and I'm not going to sit facing the wall like this. It felt very masculine, not very soft. He hadn't arrived yet, and I was thinking, I don't think so but I'd like to meet this fellow. So I remember he came in the door with his robes on and walking behind me and I don't know why that impressed me so but things just changed when he walked in and I thought, hmmm, and then when it was over and the bell was rung and we turned around on our cushions and faced him, I remember turning around and looking at him and being about six feet from him and I thought, oh I think so. Just looking in his eyes and having him look directly at me I thought this person knows more about what it is that I want to know about than anyone I've ever met. He totally understands what it is I want to understand. I knew there were millions of people in the world who knew more about other things than I did, but I didn't know anybody who knew more about what I wanted to know which was how to live completely alive. So then I went to Redwood City that night and I went about two other times before we started to meet only at Marian's. I do remember Phillip Wilson being there that first morning - those blue blue eyes. And he was like a happy precocious kid was the feeling that he had. And the way he handed me the Heart Sutra card - he was so pleased to be handing the sutra - that was the feeling. I didn't try to talk my husband Tony into coming there but I came home just so beaming every time that he said he had to come and see who this fellow was that made me so happy. And when he came it was the same for him - he really wanted to practice with Suzuki Roshi. I felt that Suzuki Roshi accepted me as a student, accepted that I had sort of given myself to be his student when one time I was gone for nine days to take care of my sister who was very ill. I missed my children - I'd never been apart from them but I lay there in bed wondering why it was I missed him so much when I had barely met him. When I came back and sat zazen and turned around he looked at me and said right away, did you catch a cold? I knew that he knew I wouldn't be staying away without a good reason. I went to my first sesshin very shortly thereafter. I'd only sat zazen six times or so. And I came to Sokoji for the one day sitting and I have to tell you what I was wearing because it's important to this story. I had on a gray soft bow neck dress which tied around and a full skirt. The women sat on one side, the street side, and the men on the other. I thought it was a little funny but I thought oh well, this is Japanese. And later Suzuki Roshi would tell us many times, he would show us his way and then we could change it but we needed to learn his way. And this was one of those areas where you gradually saw it change and become more American. But anyway, that first day I was sitting there for a couple of zazens wondering what that sound was on the floor - I was hearing that stick on the floor I thought - cause I'd seen him walk with the stick. And I thought well maybe that's to wake us up and I thought, how could anybody go to sleep in this posture. So maybe the third zazen I saw the woman next to me gasho and I saw out of the corner of my eye that he was actually hitting her, it looked like on the shoulder, and I thought, no - I didn't like that thought because it took me back to the old this is so strict and so rigid and so Japanese. I didn't like it but I thought well I gotta give it the benefit of a doubt because Reverend Suzuki is doing it and you know he wouldn't do something that wasn't for some good reason. So I tried to stop my discriminating mind about it as I'd heard him say in lecture and thought well I'll find out. So after lunchtime I asked his secretary, Irene or Ilene [Irene Horowitz], as we were washing the dishes. So she said, come with me, and she took me into his office, and she said, she wants to know about the stick and he said, I'll lecture about it at one o'clock. So one o'clock came and I sat there and I went to the lecture and the whole hour went by and he never mentioned the stick. At the time I thought he purposely didn't mention it but from knowing him more later I think he just forgot. Because his teachings for me were never convoluted or difficult like that. But at the time I wondered. So the afternoon wore on. I could always sit full lotus. It hurt very much though - it can get uncomfortable. So I was sitting in the afternoon and I thought I've never been in so much pain except when I had my babies. And I'm not gonna get anything from this because he says no gaining idea. So I wonder why I'm doing this. It must not be for me. So I thought, well, I'm never going to be coming here again, not for sesshin anyway. I'm obviously not made for this. I'll just come and hear him lecture and do a little zazen but nothing too serious because I'm not made for this. And I thought, well, since I'm not going to sit sesshin again, I'd better find out about the stick and what other way than just to ask for the stick. That's how I'll find out - a one time deal - eat the food, drink the water, ask for the stick. So I put my hands in gasho when I heard him come. And when he was right behind the woman next to me he stopped and he turned around and walked away back into his office and I was so deflated. He knows I'm a phony. He knows I don't know what I'm doing. He knows I'm just curious. So my cheeks were just hot with shame as I sat there. And then he came back and he was coming down the row and I thought, no way, no way am I going to ask for the stick and I sat just as straight as I could. And he came up to me and I kept my sitting mudra - I did not gasho. And he leaned over and whispered, gasho, in my ear. I thought, what can I do? So I put my hands in gasho and he draped over me like a soft cloud a cashmere warm delicate soft shawl, beige and brown across my shoulders and I realized I had that bowed neck on and this little bit of bare shoulder was showing and so he covered it with this woolen shawl. And the tears just streamed down my cheeks because then I knew this wasn't punishment - this was compassion. Whatever it was for, it was good. So then it he hit me with the stick and it was like the stick and the shawl were one and the teaching was so beautiful and I knew that my trust in him was totally well placed. So I kept coming.

Rhonda Johansen, Yoshida Roshi, Yachan and Ejo Katagiri - 1969 or 1970 So I got to be his driver and so did Tony Johansen, the first. We were going down to Los Altos in the morning and for a while, Redwood City in the evening. Then it became Los Altos in the morning and evening. We had the two young children so we shared the practice as best we could. Tony was great about that. And in those drives we would ask him questions and he would say I will lecture about that. And unlike the lecture with the stick he generally did lecture about the question that I asked in the car. And so that collection that Marian made of those lectures that she typed up, so many of those hearken back to the ride in the car and what it was I was asking him. The one about the waterfall is from the trip that Tony and I took him and Okusan on to Yosemite. He talked about the mountains of Japan and we thought, we should take him to Yosemite. So we took them in our little red Volkswagen bug for a day trip. And when we got to that valley and had the sun roof open, Suzuki Roshi stood open in the back with his head out the sunroof so that we were driving all through that valley with that wonderful image with him standing with his head sticking out looking at everything and he'd say, please stop! And we'd be out of the car and he'd disappear and he would leap up on rocks and he seemed to spring like a cat. And one of those rocks was by that waterfall that he spoke about. In the book it says exactly how high it was because there was a sign posted by it. And I remember he frightened Okusan and me and we were frightened for him because he was up on this huge boulder - I don't know how he got there. We would just turn around and there he'd be perched up looking at that waterfall. I saw him do that a couple of times in trees. One time in Los Altos, we were in somebody's house for breakfast and he was there beside me and the next moment he was up in the tree showing us how to prune the tree - which branches to cut off and that was one of the things he knew how to do - prune trees. And moving rocks. Being his driver was the delight of my life. I tried not to spend my time looking forward to it. But it was such a treat. And there came a point when it was such a treat that I decided that I should give it up. And sometimes I'd do it twice in a day - both times that week. So I decided that I should ask other people if they would like to do it. So I asked one couple and they couldn't do it that week and I was so delighted they couldn't. Suzuki Roshi asked Tony and me both to keep notebooks about our thoughts and feelings, how his teaching and Buddhism was fitting into our American life because he was trying to understand the culture and the American temperament and stuff. So that was the other treat of my life at that time was to be able to keep this notebook which he could read and then comment on. Sometimes he'd give lectures of something I wrote in the book and sometimes he'd even write a little comment in it. I wrote in it about my thoughts about being the driver. Should I keep driving or should I bring up at a board meeting that we should share this and I wrote I'm making such a problem out of this aren't I? or words to that effect and he wrote at the bottom of that, and this is one of the teachings I haven't understood exactly: "Speak no word. Do no doing." In a simple way it was let go of this problem, let it be. And that's probably what it was because I was making such a problem out of it. He used to say that every teaching of every Buddha was really for that moment at that place for those people or that person and that it's imperfect. It's even imperfect at that moment but it's close to perfect. So the teachings he gave to us are like that too. So over the years and having been away, I have so many things in mind, things that he said to me, and I often have to tell myself that might not be what he would say today about that.

Johansen family: Aaron, Rhonda, Toni, Chloe, Phil in Tony's arms - 1969 When we were trying to buy Tassajara in the beginning I was trying to think of ways to help raise money which I'm very poor at even for myself. So my idea was to write a story for Redbook. They had young mother's stories that they paid you $500 for. I thought I'll write an article called Dishpan Zen, An American Housewife and Buddhism. At that time it seemed very different and it affected the way I was raising my children and all. So I wrote it and gave it to him to read and he said, you're a very good writer and your writing should be based on your sitting - I remember that because I don't sit for long periods of time. But he said, you shouldn't say Roshi says so much. You should just say it because you know it's true. I couldn't explain to him that the only reason it was interesting to anybody was because of the relationship. Instead I gave it to Dick Baker for the Wind Bell and I don't know where it went. During those times when I was his driver I always felt that I expressed to him then and in my notebook that I had so much love for him and I felt so much for him emotionally that it was incredible for me. I'd never had such strong feelings for anybody. I said to him that I'd only felt anything close to this when I was in love and I said this feels like more than being in love but it's so much like that that it's confusing to me. When women fall in love, it isn't always a sexual thing unless someone invites it to be a sexual thing. And I'd had none of those sorts of feelings, but my feeling was all inclusive and when I told him in the car about my confusion, my surprise at how much I could feel for him, he said, "Don't worry. You can let yourself have all the feelings you have for your teacher. That's good. Because I have enough discipline for both of us." He was thinking about the fact that it could be dangerous for some people. At that time it could have been dangerous but it certainly couldn't be dangerous with Suzuki Roshi and he wanted me to be able to have the fullest deepest most complete experience I could have with my teacher without having to be the least bit worried. And he gave me that - it was such a tremendous gift. I wrote about it in my notebook and he wrote, "No one knows what is wrong love and what is true love. Have faith in me and yourself and your husband and let's have dinner together all four of us. But wait - I must first ask my tigress!" underlined exclamation point. So we asked them to come for dinner. We lived over in Dickey Square. We had moved to SF from East Palo Alto within three or four months of meeting him. Dickey Square was supposed to be moderate income housing. They came and there was a painted white cement wall, very prison-like except it was white in the living room which was the dining room too - it was really low income housing. I found that wall so oppressive I had taken a teal blue paint and gold paint and had outlined a couple of those blocks and painted in three others. I did it on a whim. And when Suzuki Roshi looked at it, he said, I didn't know you were a painter. He had such a way of both being playful about things and at the same time giving such recognition. We had this tiny tiny little yard where we had transplanted some rocks from a stream with moss on them and he said, you must be very proud of your rocks. He gave everything such respect. He was a wonderful guest. We had wondered what to have for them. I had never cooked for anyone but Tony and he was Danish American so that's how I cooked and I didn't know anything about this vegetarian stuff because we'd never eaten with them and it's not something that had been brought up so we had meat balls and red Danish cabbage. It was a very colorful meal because they ate it and I remember that Roshi's comment was it looks like Japanese food because the way you've done the colors and the shapes. He never said anything about the meat.

Aaron Johansen in red, holding Tony's hand and looking back towards Suzuki Roshi - Buddha's Birthday, Sokoji - 1966 Later people were so shocked at meat. We planned a big party once for the Japanese congregation. For quite a long time he was trying to make the Japanese congregation feel comfortable with his Zen students. And there was such division. They never liked to invite us to anything. Begrudgingly we'd come to things like Buddha's birthday. But Roshi got this idea that Zen students should mingle with the Japanese. [She shows me a picture she's blown up with Phillip and Kyoko] and there's Saul Warkoff and Lynn and Simi on his shoulders. Trudy Dixon's in the other photo.] Suzuki Roshi asked me to teach Sunday school so I taught it there to mostly the Japanese children and our Aaron and Ronda and Lynn's Simi and her Ann. We gave this big banquet - I think it was the last time we invited the Japanese congregation to share with us the practice - I don't mean zazen but to know that we were one group. So we gave this big party and we had a meeting at our house and we suggested having ham and this one guy said, You're not serving flesh! It was one of those serious macrobiotic types. That's the first time it occurred to me that in Zen Buddhism people might not eat meat. But we went ahead and Bill Kwong made steamed pork buns which were very good. We learned songs and Suzuki Roshi taught us Sakura in Japanese and he told me that when he came to this country and Okusan was still in Japan he'd be sitting in the kitchen and a dance band would be practicing down in the lobby and they used to play Sakura and he said that the tears used to stream down his face when he'd listen to that and think about Okusan. He said her, not Japan. He used to say, "when you light incense for your father you feel sad, but when you light incense for your master the tears stream down your face." It was helpful for me to remember that when I found out he was dying. We were in Santa Barbara - we'd been invited down by this lawyer. I'm a lawyer now so I can say it like that. And when I got a call from Katherine Thanas that Suzuki Roshi had cancer, I was of course very distraught and I called Tony and then I called the lawyer who shall remain nameless and he said to me, you shouldn't be crying - if you were really a good Zen student you wouldn't be crying at all. You wouldn't be sad because you would understood that there's no difference between life and death." I just took the phone and dropped it back on its cradle. I couldn't believe he said that. I went to bed for three days and felt like I were dying. I ached all over. I felt sick. We were called and told there would be one last tea when we'd get to come see him but he was too sick and that never happened.

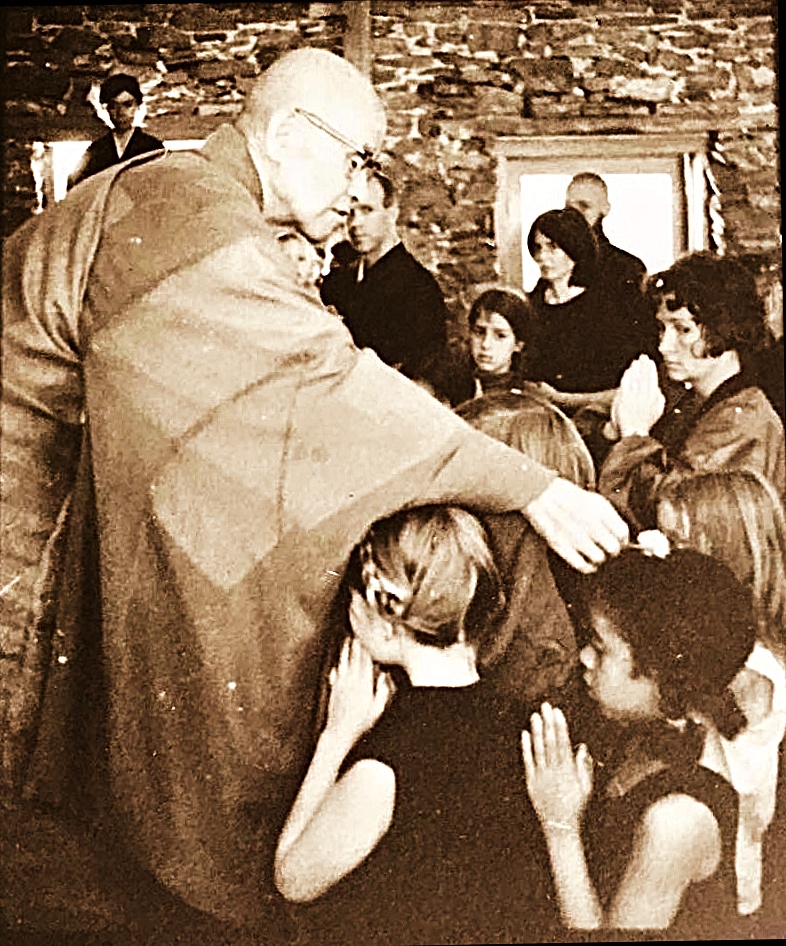

That’s Rhonda under Roshi’s sleeve, Minnie touched by Roshi’s flower, Toni Johansen in gassho, L. Walter, Kathy Cook, Silas Hoadly. But I'll tell you about my last tea with him. We were living next door. Tony was teaching at the Montessori school and Katagiri Sensei and Tomoe-san were living downstairs with Eijo and Yachan and I since have read a lecture that Katagiri gave about this family that lived above him and how noisy the children were. After Roshi died I went to study with Katagiri for eleven months. I came back to Santa Barbara because we were trying to co-parent with the kids and didn't have the money to be flying them back and forth so I came back. But after that I was up here for a short visit and I picked up a Wind Bell and read this lecture that he gave at Tassajara about this family that would cause trouble wherever they went and it really hurt because they were good friends. It was a difficult living situation and it was one of the main reasons why we left our master's temple - I'd tried so hard not to have the children disturb the family downstairs and yet let the kids be who they were. I got an ulcer trying. We were permissive parents and we had very quote good children. They were too good. They did all of our trips. Tony and I started the free school in the Haight Ashbury, the Shire School - we did all these things that our kids went along with. They were the first kids at Tassajara before there was a children's program. And then Suzuki Roshi asked Tony and me to do a children's program and to teach family practice. We did that three summers - 68, 69. We left right after that. It started with the second summer because Phillip was born. In the city we even got a television and would let them watch it for one hour so they would be quiet for one hour. And when little Phillip would get off the couch his feet would go bang. We should have traded apartments and it wouldn't have bothered them so much and I wouldn't have left. It was a very painful time to leave because Roshi was about to die and I didn't know it. At the time you were getting ready to be ordained. You know how you'd call up Yvonne Rand to see Suzuki Roshi and I would call up and she would say is it really important Toni, and I would say no it's not really important and so I didn't go. The third time she said, you know he's very busy training his young priests. He's not well and he's not strong. We didn't know he had cancer yet but we really missed him. Then we got this invitation to go down to Santa Barbara and do this Zen group down there and it was getting hard in the neighborhood for the kids to play outside and inside they were supposed to be quiet and so it seemed appropriate to go so then I did ask for an appointment to see Suzuki Roshi and I hadn't seen him for weeks. I used to see him every week and then when Tassajara got started he got busy and he went to Japan and we started the free school. We took Katagiri Sensei over to the Straight Theater, Suzuki Roshi was gone then, because we took Katagiri Sensei over to see where we were doing the school and we wanted to be sitting there and there was a great room - a dance hall upstairs with a wooden floor. But that was 67 and the height of the hippie thing and Katagiri Sensei and we sat for a few minutes and he said he did not think it was a stable enough place to do sitting and we should do it in our home. But our home was a little apartment and teachers were sleeping on the floor and living there because it was a free school. So we didn't sit for quite a while and then we moved to Sawyer's Bar in Klamath National Forest and Tony did a one room school. When I saw Roshi after we got back I said, I think we got a little lost, and he said, you can never get lost. So I went to see Roshi to tell him we were going to Santa Barbara and just to be sitting with him again was my innermost desire. I was smiling but crying because I was going and I really did not want to go at all. We didn't talk much and he said, I really miss being with my older students but I have a lot to do and ZC's very big and I want you to know that I miss being with you which just made me cry more and he must have told me five times, put some more honey in your tea and it got so thick with honey I couldn't drink it but I did. Maybe he just said it three times. And I said now that I'm here with you the thought of going to Santa Barbara is very very difficult and he said with his little impish smile, well you go and you start a temple and I will come and retire in your temple. I knew he didn't really mean it but it was sort of like, hold that thought. I knew that he'd come down for sesshins or a visit or a weekend off maybe. So I would let myself hold that thought that he was coming after I left. And I kept an empty room at the head of the stairs that was Roshi's room for when he came and then I got that call that he had cancer. He told us he was sorry for dying so young. He said, he was just a baby Zen master, only 66 and he should live to be 99 but he wanted 10 more years so that those of us who were in our thirties would be in our forties and those in our forties in our fifties and we would be more ready. We don't need our teacher but we want our teacher. I was 32 when he died and I did go look for a teacher on and off which was hard to do because I had the children. Tony and I ended up getting divorced.

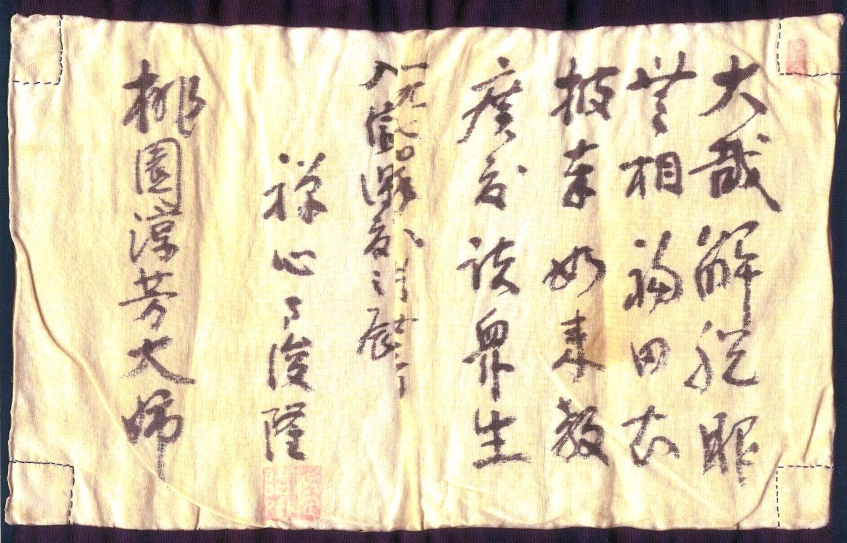

Suzuki Roshi's calligraphy on Toni Johansen's rakusu Our Buddhist names was one of Roshi's funny little kind of jokes. He named me Toen Jundo which means essence of a plumb blossom or something like that and he named Tony something that starts with an R who was a Zen master who went up to the top of a mountain to seek his enlightenment and he didn't get it and when he came off the mountain he saw a plum orchard in bloom and attained enlightenment. I thought that part of my practice was being married to Tony because Roshi said, you should keep family practice. And somehow when he wasn't there anymore I didn't do family practice anymore. This is more emotional than I thought it would be - telling you because you were there. Mostly I asked questions in the car and when we had dokusan I wouldn't have questions, there were no questions. It was completely clear so I didn't ask any. We would just sit quietly for ten minutes or so - I didn't want to take too long. I would end it - I would gasho. Then when I was by myself I'd think of all sorts of questions and then when I'd sit with him there were no questions. One time he said to me, do you have a question and I said when I sit with you I have no question, everything is clear, and he said you have what we call awakened antennae and he said it in Japanese. I'd like to hear that term again. When you're with me you have my enlightenment. You know he wouldn't talk about enlightenment as if it were the type of thing that one person had and another didn't have. And then he'd talk about it as if it were the type of thing that one person had and the other didn't have and could get from the other. And he'd say we're all enlightened and it will be no difference if you have an experience that then you are enlightened. It will feel the same. Notes from Toni after podcasts in 2024 The summer of 19 ? Lynne Warkov and I were asked to facilitate a children's program at Tassajara for the children of practicing students. Participation was always an option for the children, not a requirement. The kids ate meals together, and gathered for tea time with the rest of the community, a favorite time for all! It often provided an opportunity to be with Suzuki Roshi. They choose their own activities during the day, joining in group projects, or pursuing individual interests. Some occasionally chose to join in work projects such as drying apricots, or harvesting vegetables. Others were inclined to seek out their own endeavors, surprising us with their creativity. There was a dramatic rendering of the indigenous tale, "When Coyote Made Man," and a pool extravaganza with seals and Mermaids Cym Warkov, age six, was asked what she'd like to do. "Bake bread!" She was instructed to go to the kitchen and ask the head baker who at first discouraged her. The requirements were rigorous. "It's too hard," she was told, "you would have to get up at 5:30." But she wasn't disuaded, and surprised us all by following the proposed schedule to a T! She persevered for days, baking Tassajara bread to her heart's content. Especially gratifying was the way children sewed their own rakusus (except the babies.) They took it seriously, preparing for lay ordination with Suzuki Roshi. Tomoe Katagiri was instrumental in teaching the children the way of sewing rakusus. The children included in the ordination ceremony were the following: Diane di Prima's - Alex and Minnie; Johansen's - Rhonda; Walter's - L. and Eliot; Petchey's - David, Julie, and another daughter; Warkov's - Aaron and ?; and Katagiri's - Ejo and Yasuhiko - right? That would be 12. I think there were 12 in the ordination. What about Monica Linde whose parents were Jed and Maria? - dc. Both Lynne’s son and my first born son are named Aaron, coincidently. My 1 and half year old son Phillip was in the ceremony with Tony. Phil wore the rakusu I sewed for him. He was named after Phil Wilson. He was given the Buddhist name Katsu Zen which translates (I think) as Vivid Active Way. That I just learned was the name given Phil Wilson! Aaron’s Buddhist name was Sho Shin — beginner’s mind! On days with four or nine in the date, the kids enjoyed joining students in the trek to the Narrows. With packed lunches they eagerly took to the trail, anxious to slip into the pool at the Narrows. This was a highlight for everyone. Students and children alike. *** I don’t think what Lynn and I did was child care per se. It was a program for the children who chose it, not a requirement. There were some activities that were more structured, such as introduction to zazen, but even that was optional.We had optional work in the garden, with some of the students taking to it, other students free to find their own activities. We gathered together for meals, and for the ever popular tea time with the rest of the community. A group of the kids created a play called “The Day Coyote Made Man,” based on an indigenous tale. There was also a water show, with mermaids and seals in panty hose. Mainly the children were free. Photos of children at Tassajara: SR0396, SR0397, SR0398, SR0399. |